Career Frameworks 🪜

What they are useful for, how to use them, and the various styles and examples

This week we dive into one of my all-time most requested topics: career frameworks!

Over time I received all kinds of questions about it: from founders who are in the process of creating such a framework for the first time, to engineers who want to use it for growth, to hiring managers who struggle to keep it up to date.

To make sure I am thorough about it, I will split this into two consecutive editions:

1️⃣ Part 1 — this one will cover definitions, why and when you should use a career framework, and some good examples.

2️⃣ Part 2 — the one coming up next week will cover how to create one that fits your team, and how to roll it out properly.

So, here is the agenda for today:

📌 What is a career framework — definitions first.

🗝 How to use it — what are the practical use cases where it brings value?

📆 When you need it — when is it the right time to create one?

📚 Styles and Examples — let’s cover some of the most famous frameworks out there.

Disclaimer: career frameworks do exist for all kinds of jobs, but I will focus here on engineering teams. Some of the general advice may apply to any department, but the details and examples will be centered on the tech space.

Let’s go! 👇

📌 What is a career framework

In its most basic form, a career framework is a document that covers two things:

🪜 Levels progression — the various roles and levels people can perform in the team, and how people can advance from one to another.

🎓 Competencies — skills and responsibilities that are expected of people in each role.

Other things that are sometimes included are:

📋 Track record — for each role, what you should exhibit to get promoted into it.

💰 Compensation — for each role, salary bands, equity, bonuses and other forms of compensations.

Why is this useful?

A career framework is to managers what regular docs are to engineers and PMs. It creates alignment and makes their jobs easier:

For managers — it reduces the room for personal judgment and mistakes.

For everybody — it provides clarity about their growth path.

So how do you use it, in practice?

🗝 How to use it

In my experience, career frameworks see practical usage in three main scenarios:

1) Hiring 🎒

A clear definition of roles and levels is immediately useful in hiring. Joel Chippindale, CTO coach, reports 👇

In smaller companies I have found that much of the work to define roles and levels has been driven by the need to hire. For example if we are going to work together to hire a "Senior Engineer" then we need to have a shared understanding of what we expect from a "Senior Engineer".

Then it is only a short step to start using these definitions to help have conversations about professional development.

Starting in this way enables the team to start small i.e. think about one role/level and practice using these expectations in real conversations about hiring and professional development before building up a wider framework.

The career framework also makes for good hiring material. Candidates may ask hiring managers to have a look at it to assess where they would stand in the wider org, and their own opportunities for growth.

As a candidate this is a smart move, and you should consider it a red flag 🚩🚩🚩 if the hiring manager refuses to make you see it, or if the company is above a certain size and doesn’t have one.

2) Growth framework 🌱

Writing down duties and expectations for each role / level empowers people to take ownership of their own growth. People can check how they should behave to get next level, and go for it autonomously.

A good framework also recognizes a variety of valid career tracks (e.g. individual contributor vs manager), and makes people understand how to move between them.

This is all work that is lifted straight from the managers’ shoulders. Managers can spend less time informing people about how things work and what is expected of them, and more time coaching them about how to do better.

This common ground is especially useful in reviews 👇

3) Reviews 🔍

Without a career framework, reviews and promotions are mostly the result of managers applying their own judgement on people. A manager’s personal judgement is, of course, important, but is also problematic, for many reasons:

Biases — we all have biases, hidden or not, that impact our decisions. Such biases often affect fairness and diversity. When dealing with people’s performance, we need to minimize bias and stick to objective assessment.

Personal beliefs — without a clear framework, managers stick to what they believe to be needed by each role, which isn’t necessarily aligned with what other managers believe, or the rest of the company altogether.

Politics — the more room for personal judgement there is, the more politics will develop within the company. People will look to please their manager and behave according to their personal quirks. A certain level of this is inevitable in any company, but it is greatly reduced by creating good common ground around roles and levels.

📆 When you need it

I like to think of the career framework as a process rather than a document. It is a living thing that grows with your company, starting simple and getting more sophisticated along the way.

One mistake that I often see is tech leaders looking at famous examples of frameworks, like the great one from Rent the Runway, and thinking: “This is too complex, I don’t need such a thing”, and giving up.

But you can start small. Or better, you need to start small — because if you wait too long to do something about it, when the time comes you will be in trouble.

Here is my advice about timing and starting small:

1) Start with principles 🌟

As long as you are a small team of less than 10 engineers, you might just be a group of smart generalists without specific roles.

In this case, just create a set of engineering principles that reflect your values. These should provide general guidelines and serve as a basis for a future framework.

2) Wait for an inflection point 📈

You can go a long way just with good principles that you periodically review with your team. It comes a time, though, when you should expand those into full expectations about different roles and levels.

In my experience, there are two main inflection points that lead to this:

↕️ You clearly have different seniority levels — when it’s clear that some guys are way more experienced than others, you should sit down, separate levels and clarify your expectations for them.

👑 You have managers — as soon as you introduce managerial roles, you should write down what you expect from them and what is needed by other folks to get the job. You should do it even if 1) they are just part-time managers, or 2) there isn’t the opportunity for others to move into those positions (even merely because of your headcount).

A common fallacy is thinking that just because a role / level is defined in the framework, then there should always be the opportunity for people to get that job.

Not all opportunities are available all the time. You might not have room for another manager, or another Staff Engineer, and that’s fine — just be transparent with people about this.

📚 Styles and Examples

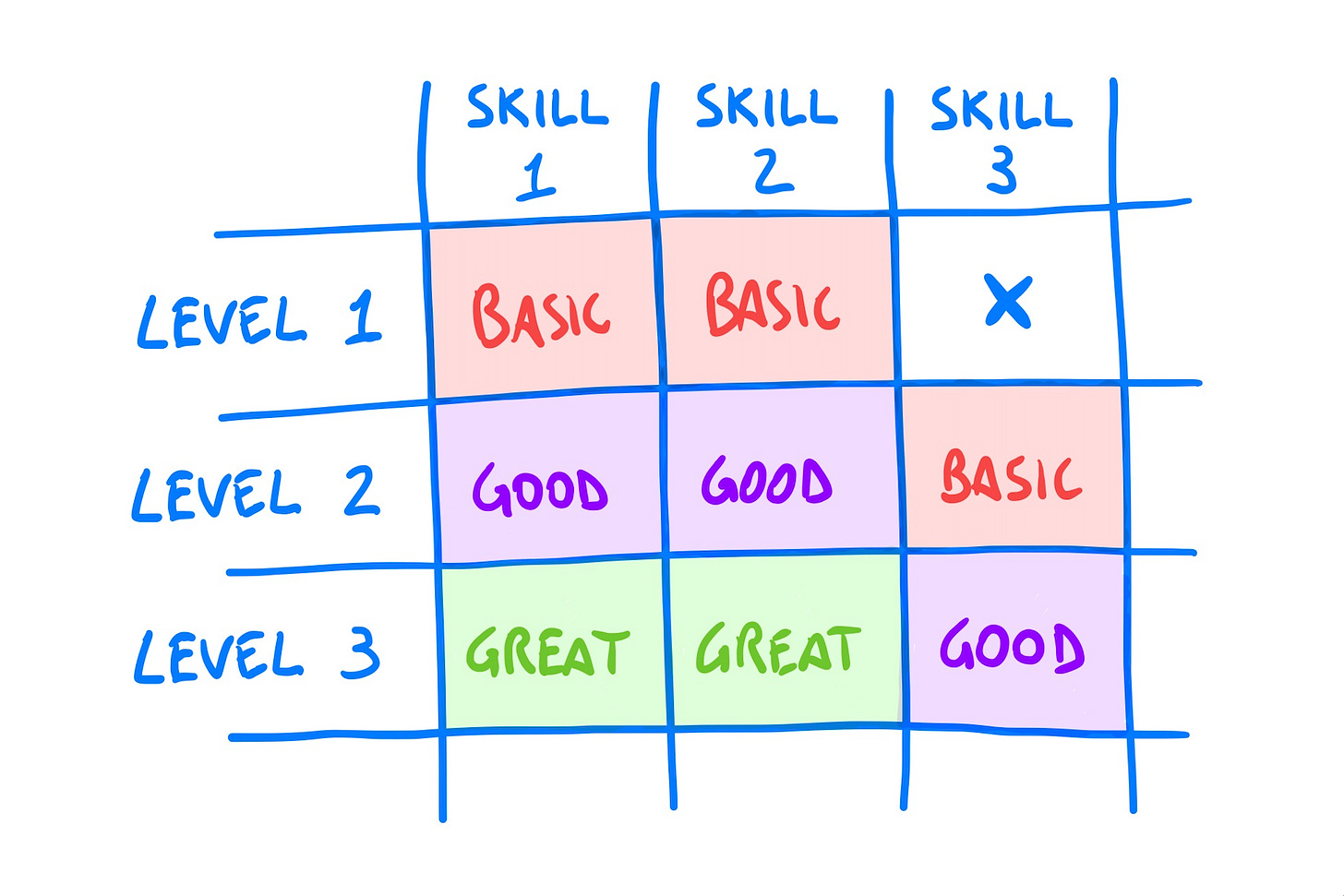

Most career frameworks feature combinations of three main concepts: skills, roles and tracks:

Skills — areas of competence of people. Here you separate between things like tech skills, leadership, impact, and more.

Roles — with levels. Here you separate between engineers, senior engineers, engineering managers, etc.

Tracks — how people can progress through the various roles. An individual contributor track features different roles than the manager one.

Let’s see how you can use them to create different styles of frameworks 👇

1) Matrix Frameworks ✖️

Since skills can be the same for all roles (at least in the same track), but you expect different levels of competence for each role / level, a common approach is to represent those combinations of skills * roles with a matrix.

Great examples of matrices are:

Rent The Runway — created by Camille Fournier. One the most influential career frameworks out there.

CircleCI — a sophisticated example where skills are also organized into areas and themes.

The main benefit of matrix frameworks is that they bring clarity and allow you to be thorough with expectations. A set of skills that covers all areas of competence and works well with your culture is an investment that pays off in spades in the long run.

However, it also requires a ton of work. In order for the framework to be useful, each skill / role box should be carefully crafted and then actually used in performance reviews.

My recommendation is to invest in this once your product / team gets to a level of maturity that makes you comfortable that these abstractions will stand the test of time. Of course frameworks need to be updated over time, but you don’t want to mess too often with adding / removing entire skills or changing their definitions, as people rely on them for growth.

If the matrix is too much for you, there is a simpler alternative 👇

2) Simple Level Progression 🪜

The main challenge of matrix systems is defining a set of skills that will stay relevant, and for which you can write separate expectations for the various levels.

This might be too much at your stage. In that case, you can skip the skills part and just focus on good descriptions for each level.

For each level you write down:

Expectations — the work people are expected to do at this level.

Competencies — the qualities they need to exhibit.

Track record — what people need to have achieved to be eligible for that level.

The next step in this work will be to factor out competencies over time, which turns this scheme into the equivalent of the matrix approach.

Etsy has a good example of this.

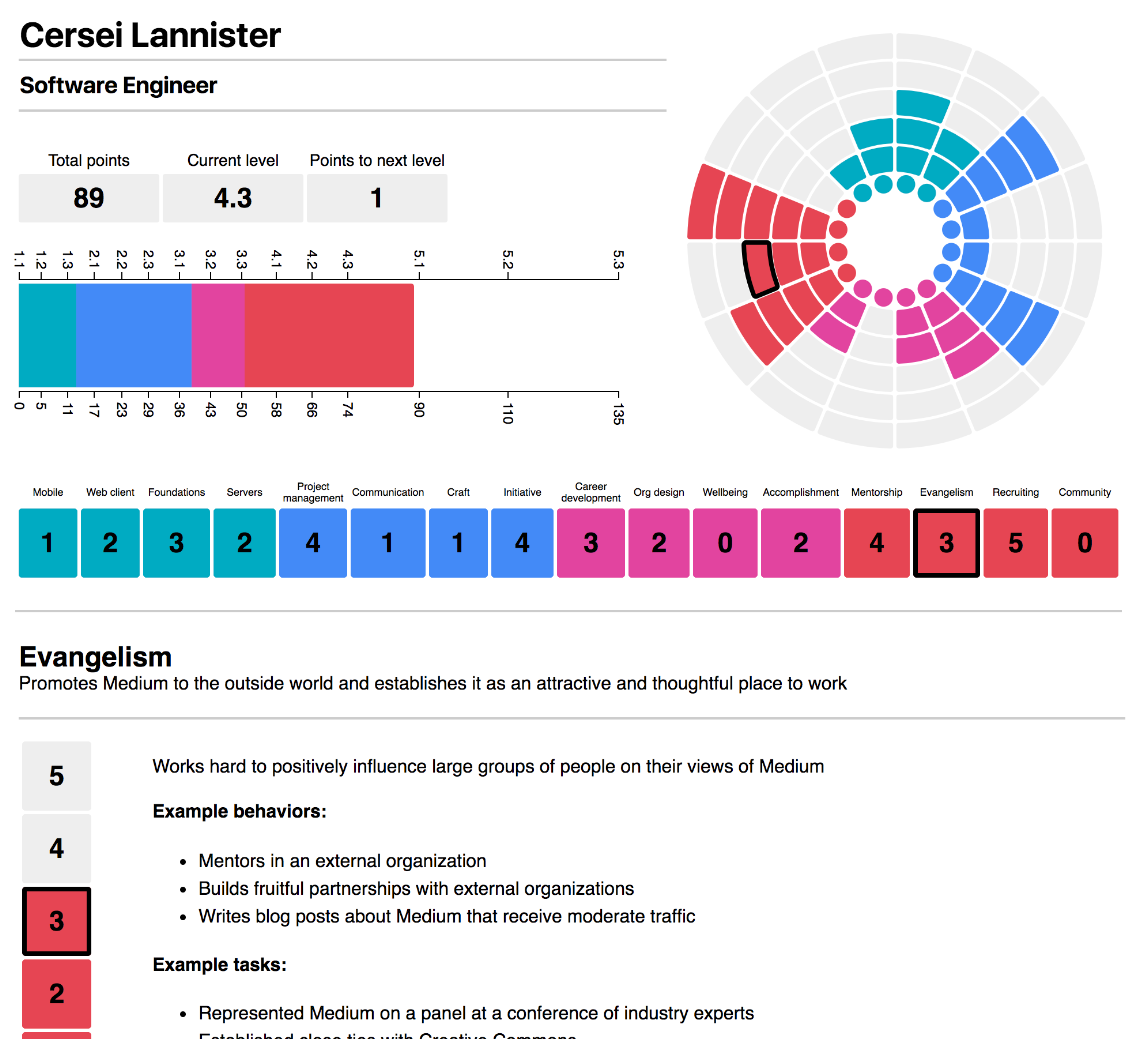

3) Skill-driven 💠

The examples above have a strong focus on levels. Skills exist to create expectations around levels — and people are mostly defined by what role / level they belong.

There are alternatives where the strong focus is on skills, rather than levels. Frameworks like Medium’s Snowflake (not used anymore, but yet!) aim to describe precisely people’s qualities, without being 100% prescriptive about roles.

The Engineering Ladder framework by Jorge Fioranelli is similar, in that it focuses on assessing people’s qualities first. Once you have this information, you can use it to assign people to the appropriate levels.

This approach is interesting because it gives you an assessment that you can use in many ways, like for moving people across different roles or assigning part-time responsibilities.

It is also tricky to pull off, though. Having a large number of skills, like Medium, easily causes a lot of work when it comes to assessing where people stand — not to mention when you are hiring someone new.

Finally, it is not trivial to figure out how to match skill levels to roles. When you have 3-4 skill sets, you can safely require people to meet all expectations for each level. You can’t expect the same when skills are 10-15.

Medium used to be strict about this — they summed up the points that people scored and defined milestones based on them. Later, though, they also backtracked from this 🤷♂️

📌 Final thoughts

When choosing a career framework style, you should consider why you are introducing it in the first place. Career frameworks align people around expectations, growth, and hiring.

The level of sophistication of the framework should match that of the problems you want to solve, and not more:

In a team of 5 people, expectations are probably the same for everybody, and alignment means just writing down a few engineering principles.

In a team of 10-15, you may get away with creating 2-3 simple levels, with descriptions of a couple of paragraphs each.

As soon as you have managers or leadership roles, you may identify a few core skills and write down the different expectations for the various jobs.

In a large organization, you may try a more granular assessment of your people’s skills to help with internal mobility and the deeper career tracks.

And that’s it for now! See you next week with the second part, which focuses on how to practically create a good framework for your team, and how to roll it out!

See you next week!

Luca

Great article!

Hoping to add some value, I have compiled a series of real-world career ladders: https://www.leadinginproduct.com/p/product-management-career-ladders

Don't adopt them right away, but use them for inspiration.