How to Run Performance Reviews 🥇

A first-principles approach to performance management + a practical workflow + wild ideas from successful companies.

In any company, you would be hard pressed to find any process that impacts people’s behavior more than performance reviews.

People may ignore the company’s mission, principles, and the supposed culture, but never ignore how their performance is evaluated. For this reason, reviews have the power to shape culture more than anything else — by rewarding good behavior and correcting bad one.

Yet, there isn’t much consensus on how to have them.

Sure, we have plenty of examples, usually from big tech, but most other companies use their own recipes, which are sometimes similar, sometimes remarkably different.

Some companies don’t have reviews at all, some run committees, some run peer-based processes, and more.

So, today, like we often do on Refactoring, we will unpack this by reasoning from first principles. We will figure out the goals of performance reviews, list various approaches, and evaluate upsides and downsides.

Here is what we will cover:

🎯 Why we have reviews — let’s not take anything for granted.

🍱 What goes into a review — work summary, feedback, and goals.

🙋♂️ Who contributes to the review — the role of subjects, managers, and peers.

🤝 How to have the review — a practical, step-by-step process.

🔀 Alternative approaches — case studies from unconventional companies like Valve, Netflix, Morning Star, and more.

📚 Resources — templates, articles, and books to learn more.

Let’s dive in!

🎯 Why do we have reviews?

Reviews are personal conversations about growth and career. You hold them to provide feedback and set people on a growth path.

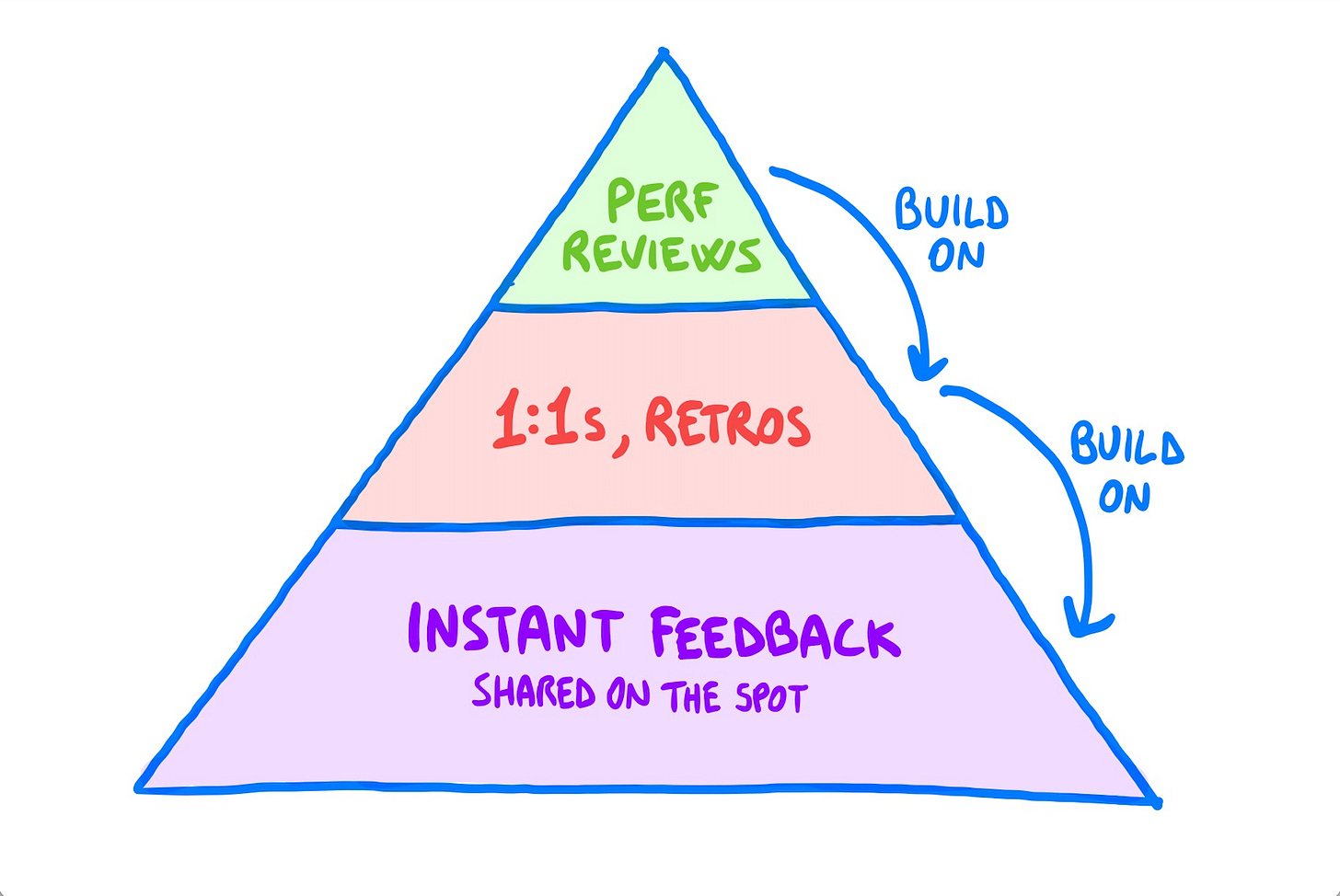

Of course, reviews aren’t the only time (hopefully 🙈) where you touch on these topics: good feedback is continuous — it happens daily, in 1:1s, retros, and more.

Such moments, though, are mostly tactical. They are meant to steer the ship to catch more wind, or to avoid a storm. Reviews, instead, are strategic. They are when you take out the map, lay it on the table, and decide where to go.

This difference is similar to what you see in other processes, like planning. Weekly cycles and (e.g.) quarterly goals complement each other. If you only ran weekly sprints, you would end up doing mostly small, iterative improvements. If you only did quarterly planning without frequent check-ins, you would set goals but likely diverge from them.

So, for this reason, it’s always a good idea to have performance reviews, regardless of your team size. Small teams and startups may hold simpler reviews, because planning is uncertain or career frameworks are simple (or absent), but some version of them is always useful.

🍱 What goes into a review?

A good performance review includes three main things:

📋 Summary of your work — during the last period.

🔍 Feedback about your performance — during the last period.

🎯 Goals and priorities — for the next period.

There are more conversations that descend from these, most notably about promotions and compensation. But they do not strictly belong to the review itself, and I also argue you should have them separately (more on that later).

Moreover, for any of these items, there are three types of people who can contribute: 1) the subject of the review (with self-reviews), 2) their manager, and 3) their peers (with peer reviews).

These all have a crucial role. Let’s look at what goes into a review from the perspective of a manager, and then cover self-reviews and peer reviews 👇

📋 Work Summary

The work summary includes projects people have worked on and what they specifically did in them, including notes on scope, impact, collaboration, and more.

You need to get this right, as it is the common ground on which the whole review is built.

You can find a lot of advice online about how to get this right, which mostly says to go through everything your reports have done, just in the weeks/days before the review. Now, while you definitely need to dig through tools and docs, I have found that if you only rely on this, you are in for a bad experience.

In fact, when you go through stuff (e.g. design docs, emails, issue tracker) that is months old, most often you don’t have the context for a fair judgment anymore. Not to say that it’s a ton of stuff. Multiply that by, I don’t know, 6-7 reports, and it is just unbearable.

So, as engineers, one of the things we are good at is splitting big tasks into smaller ones that are easier to handle. My preferred way of splitting this is by keeping a journal about my reports.

The journal includes my notes about what they did and how. It isn’t for tracking who did what — you have tools for that — it is for storing my impressions: how they acted on feedback, how they worked with others, how they handled deadlines, and more.

I use these notes in two ways:

🧑🤝🧑 1:1s — I use my notes to prepare for 1:1s. The 1:1 agenda is mostly set by my report, but if I see that the conversation stagnates, I can route it to some items from my notes.

🏅 Performance reviews — notes give me context about stuff that happened during the period, so I can more easily catch up. They act as anchors to recollect things from my memory, and complement what I can put together from tools and docs.

I don’t have a template for such notes: I just keep a page for each of my reports and jot down quick thoughts there every once in a while, possibly with links to other stuff. Then, some weeks before the review, I go through the notes and combine them with the rest of the materials.

These notes are private and are not shared with my reports, as opposed to e.g. the 1:1 notes, for which I usually create a shared page with my report.

🔍 Feedback about performance

Performance reviews are first and foremost a big moment of feedback. So, most advice about giving good feedback also stands for the feedback you give in performance reviews.

Nicola wrote a fantastic article about this 👇 which is also one of the most popular ever on here.

Two key points are:

🪟 Make it clear — good feedback is specific, grounded in examples, and actionable, so that people know what to do with it. This stands true both for good and bad feedback: just like you wouldn’t say to anyone “you are bad”, you shouldn’t equally say “you are doing great”. What is it they are doing well? Why?

⚖️ Make it balanced — people should receive feedback on all the spectrum of their behavior, which means that most feedback is usually reinforcing, rather than corrective. Research indicates that in the highest-performing teams, the praise to criticism ratio is >5:1, that is, people receive more than five positive comments for every negative one.

Sharing balanced feedback is especially important in performance reviews, where feedback acts as the foundation for setting personal goals and priorities. I see many managers setting goals mostly based on issues and personal gaps. Those are ok, but you should also double down on what works. What are the strengths of your report? What are they naturally inclined to?

We must have a clear development plan (PDI) after each performance review with clear to do's and deadlines not only for the main 3 gaps ("needs focus"), but for the 3 main strengths as well (over-perform). As managers, we have to be careful to not focus on the gaps and forget to enhance the strenghts, which are the person's differential and differentiate them from others.

— Gabriel Bechi, Head of Business Ops at G4 Educação

The goal is not to shape a perfect, all-round professional who is equally good at everything — nobody is — but to figure out the journey that is ideal for their aspirations and their impact on the business.

🔄 Feedback is continuous

I believe performance reviews are mostly useful for acting on feedback — by setting goals and priorities — rather than sharing it.

In fact, in healthy relationships, feedback is frequent and mostly shared 1) on the spot, and 2) in recurring venues like 1:1s. So, feedback in performance reviews should mostly ratify what has already been discussed privately.

As a rule of thumb, if people are surprised by your review, you did something wrong.

🪜 Career frameworks

Career/skill frameworks are somewhat a prerequisite for good performance reviews. In fact, they provide a benchmark to set expectations against, ensuring reviews are fair across the company because less reliant on subjective judgment.

They also provide a blueprint for setting goals, having career conversations, and they generally make a manager’s job easier by lifting a lot of what would otherwise be on them.

That said, you should have reviews even if you are a small company and you don’t have a career framework. Yes, these will look more like informal talks with managers, will be subjective, not necessarily fair — but it’s better than nothing.

🎯 Goals and priorities

During a review, you should set a few personal goals for the next period.

I like these to be orthogonal to regular team activity. That is, to focus more on the how rather than the what — as the latter goes through regular planning.

Some examples are: